A-D

E-H

I-N

O-R

S-T

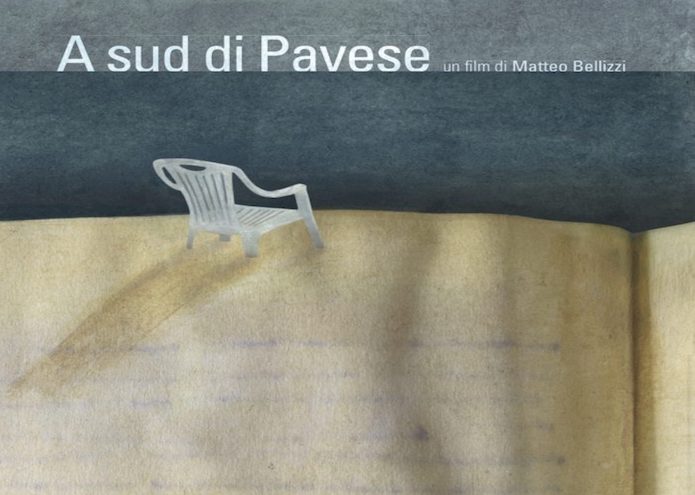

The figure of Cesare Pavese, one of the greatest writers of the 20th century, provides the inspiration for an intimate journey in search of the threads that still tie his universe to the present. Shot in the symbolic places of his poetic imagination, the film sets out from the hills of Piedmont and travels to the shores of Calabria, where the writer was interned, via the Macedonian communities that are repopulating peasants’ vineyards and stories of people who are still resisting in difficult areas, in some cases in the name of literature. A sud di Pavese is a homage to a force that goes beyond cultural references, it’s the exploration of an area in which life and literature are so interwoven that the borders between them are lost.

A sud di Pavese begins with a return, more than ten years on, to the places where I shot my first short documentary, “Filari di vite”. Even then I wanted to look for Pavese in the present, among the last peasant farmers, who looked as though they came straight out of the pages of his novels. That was my encounter with the “myth” Pavese spoke of (mythic is an event that takes place outside space and time) and it marked my view profoundly. To return is to perceive the twilight of a world, to go beyond the literary references themselves to see what is still left.

Pavese thus became the lens through which I reinterpreted reality, looking for stories where he found his, as if those places were still active wellsprings.

Matteo Bellizzi

Italia / 2015 / 56 min.

Directed by: Matteo Bellizzi

Production by: Stefilm

Sowing poetry is good for the earth

Cesare Pavese was well aware that poetry doesn’t exist per se, but has to be dug out a bit like looking for a mushroom in a wood. One rhythm of the many whose tempo fragments, amid the thousands of possibilities it has to articulate a story. Most of all, Pavese was well aware that poetry is first and foremost a connection between the seeker and a world that hides away or takes no notice. It’s the miraculous, fleeting, even illusory chord between the inner rhythm of the globetrotter – his heart, one might say – and things. There’s a moment, an unpredictable moment, in which the two rhythms beat the same time. But it doesn’t last for long, which is why poems are so brief. It’s a sort of gift to the world and it’s also the most poignant of illusions: that man has a seat in an orchestra and that the life we happen to be living is a musical score. Someone is aware of the point when the notes will bring down the curtain.

In this sense, Matteo Bellizzi’s A sud di Pavese (To the South of Pavese) inherits a legacy. In this film, so dense and so moving, there is, first of all, the idea that trying to tune one’s heart to the world is much more than a consolation, that it’s a discovery and, ultimately, a way of resisting mounting ugliness. Bellizzi slides down Pavese’s Italy from the Langa district in the north to Brancaleone Calabro in the south, taking with him not so much the author’s imagination as his poetry. He tries to see how much room we’ve left for poetry, aware that if the question is rhetorical and that the answer could be rhetorical too, the game isn’t over, at least not yet. There’s no room for poetry, you might say, in the illegal building he finds in Calabria, there’s no room for poetry in the clapped-out old people in rest homes, taken away from the land that used to feed them.

Yet poetry is, above all, the evasion of rhetoric, and this is where the greatness and beauty of A sud di Pavese lie. For Bellizzi slides down the whole length of Italy leaving poetry every metre of the way. There’s something deeply creatural about the love with which life — including human beings and their clumsy attempts not to succumb to pain — appears on the screen in this film. Bellizzi sows poetry behind him, which is one way of trying to get back on the right track. What he leaves at the end of the film is a compassion that disarms even the most cynical score to settle with the world. And as the credits roll, one is wrapped in a great melancholy, and this is another, arguably the most important, of Pavese’s legacies. Namely the idea that melancholy is not a defeat, but only one of the many forms that things take on in the eyes of those who have to do with them. And that there’s a beauty and a poignancy in every leave-taking, without it having to be, per force, a surrender.

Andrea Bajani